Can AI Self-Correct? Analyzing the Limitations of Large Language Models

19 Mar 2024This post is a summary of this research paper writen as a final project for Stanford’s CS 224N and Intro to AI Alignment classes.

As models become more and more powerful, they have started to approach or exceed human-level performance on a variety of tasks. In order to train these models, researchers have been using increasingly large datasets and more compute. However, as these model approach human limits, it becomes harder and harder to improve them from human feedback.

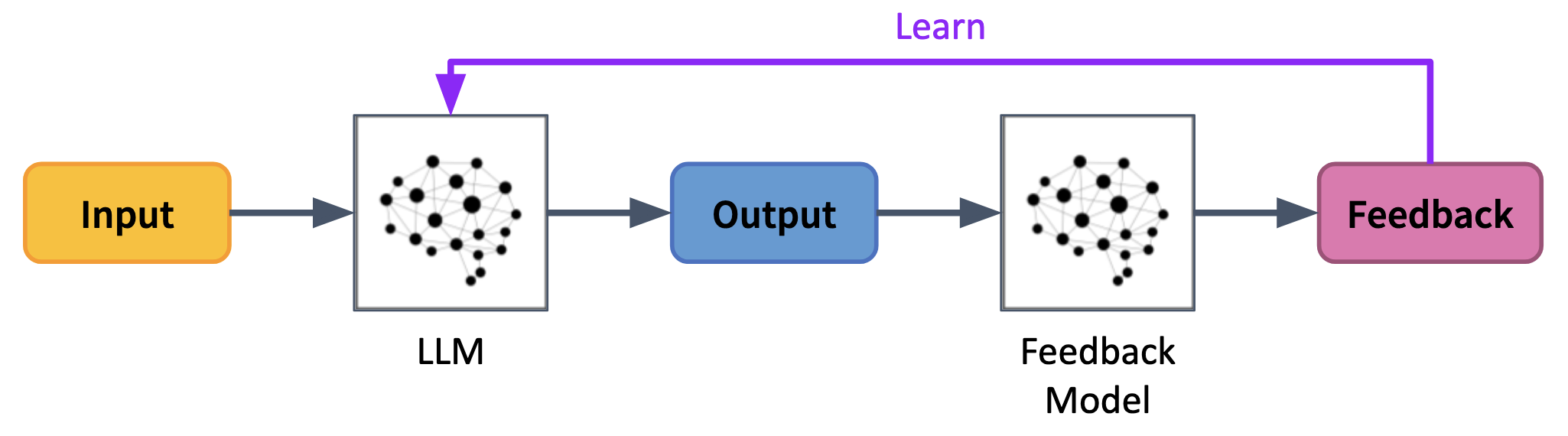

The natural solution is to replace the human feedback with model feedback; that is, to have the model evaluate its own outputs and make necessary amendments. There are several varients to this process, including RLAIF1 and Constitutional AI2, but the basic idea follows the following abstract process:

However, this method operates under the assumption that the feedback is actually aligned. Researchers have shown that these models can be easily swayed by biased feedback, which might hint at a fundamental deficit in their ability to self-correct and result in runaway feedback loops if used in an RLAIF pipeline.

There are many proposed methods of improving reasoning ability/feedback including:

- Self-Consistency

- Tree-of-Thought

But these approaches tend to rely on model variance to improve performance which can get very expensive depending on the number of inference calls needed.

The Challenges of Self-Correction

The idea behind self-correction is relatively simple. If you give an LLM a mathematical problem, it should be capable of identifying any errors in its own solution, just like a human might. After all, humans learn almmost everything they know through trial and error and interpreting feedback. In an ideal world, models could review the problem, correct the error, and generate a more accurate solution.

Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple.

Recent results suggest that while LLMs are fairly good at correcting several reasoning tasks, they struggle to identify mistakes in mathematical reasoning. Intrestingly, they are often capable of correcting their errors when the errors are explicitly pointed out, but struggle to identify these errors themselves 3. Thus the question arises: why do these models struggle to find their own mistakes?

In this post we will explore the validity of the feedback step in this pipeline, and whether it is possible for AI to self-correct mathematics.

Base Models are Overconfident

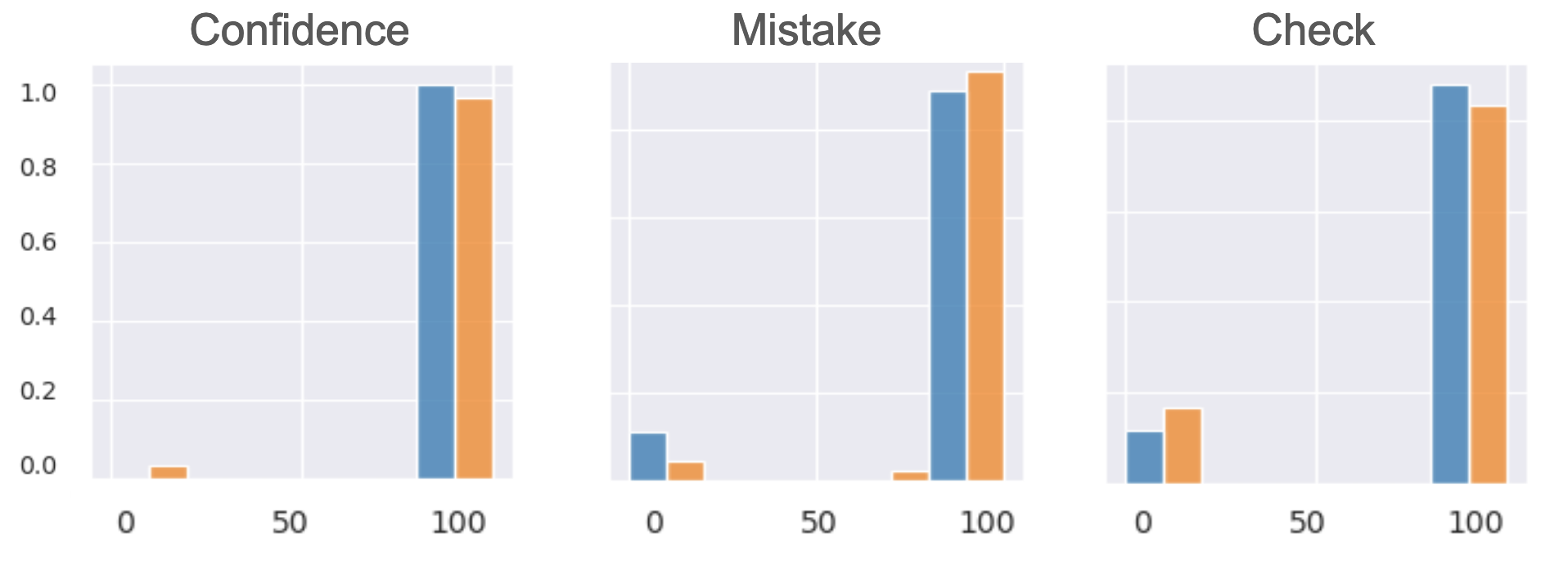

We begin our investigation with LLaMa-2 7B and evaluate on the GSM8K and Hendrycks MATH datasets. Due to the sensitivity of model performance to specific prompts, we tried a wide range of prompts across three categories:

- Confidence: We asked the model to evaluate it’s confidence the given solution was correct.

- Mistake: We asked the model to find mistakes in the solutions.

- Check: We asked the model to double check all of the calculations.

Additionally, we tried several different rating scales

- Percent: the models rates its confidence in the correctness of the solution on a scale from 0 to 100%

- Rating: the model rates the accuracy of the solution on a scale from 1-5

- Correctness: the model outputs “correct” or “incorrect.”

- Confidence Level: the model outputs its confidence as one of “very confident,” “confident”, “somewhat confident”, “not very confident”, or “not confident”

We found that there was not a massive difference in performance between the four different scales. It is important to note that we rescaled each of the rating scales to be between 0 and 100 so it was easier to compare between the prompts.

We find that LLaMa-2 7B is overconfident in the correctness of its solutions. It is possible this is the result of sycophancy, where the model is trying to please the user by giving a high confidence rating. This is a common problem in AI, and is often the result of the model being trained on biased data.

Finetuning for Self-Correction

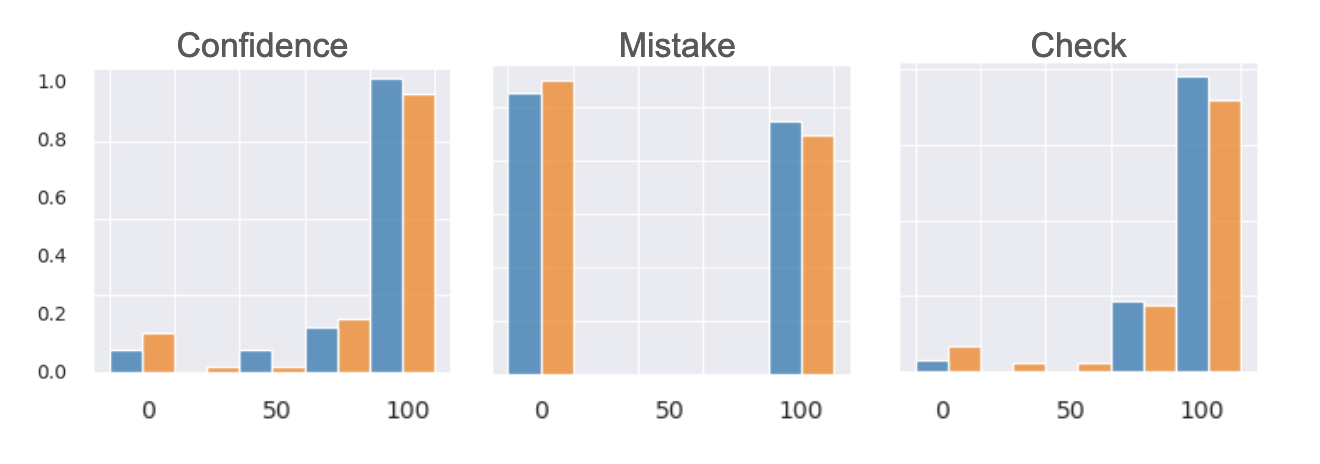

Thus it makes sense that we would be able to reduce this overconfidence by finetuning the model to produce better feedback. To test this, we finetuned LLaMa-2 7B on a ~40k dataset of feedback generated by GPT-4 where GPT-4 was given both the generated solution and ground truth solution during the feedback process 4. We used LoRA to speed up the finetuning process.

We found that finetuning the model did indeed reduce the overconfidence of the model. However, it did not improve the model’s ability to differentiate between correct and incorrect solutions. We conducted a Mann-Whitney U test to determine if the difference in between the distribution of confidence ratings for correct and incorrect solutions was statistically significant. We found that the difference was not statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.05 and regardless of prompt used.

Thus finetuning simply increased the calibration of the model, but did not improve the model’s ability to differentiate between correct and incorrect solutions.

Why do LLMs Struggle to Self-Correct Math?

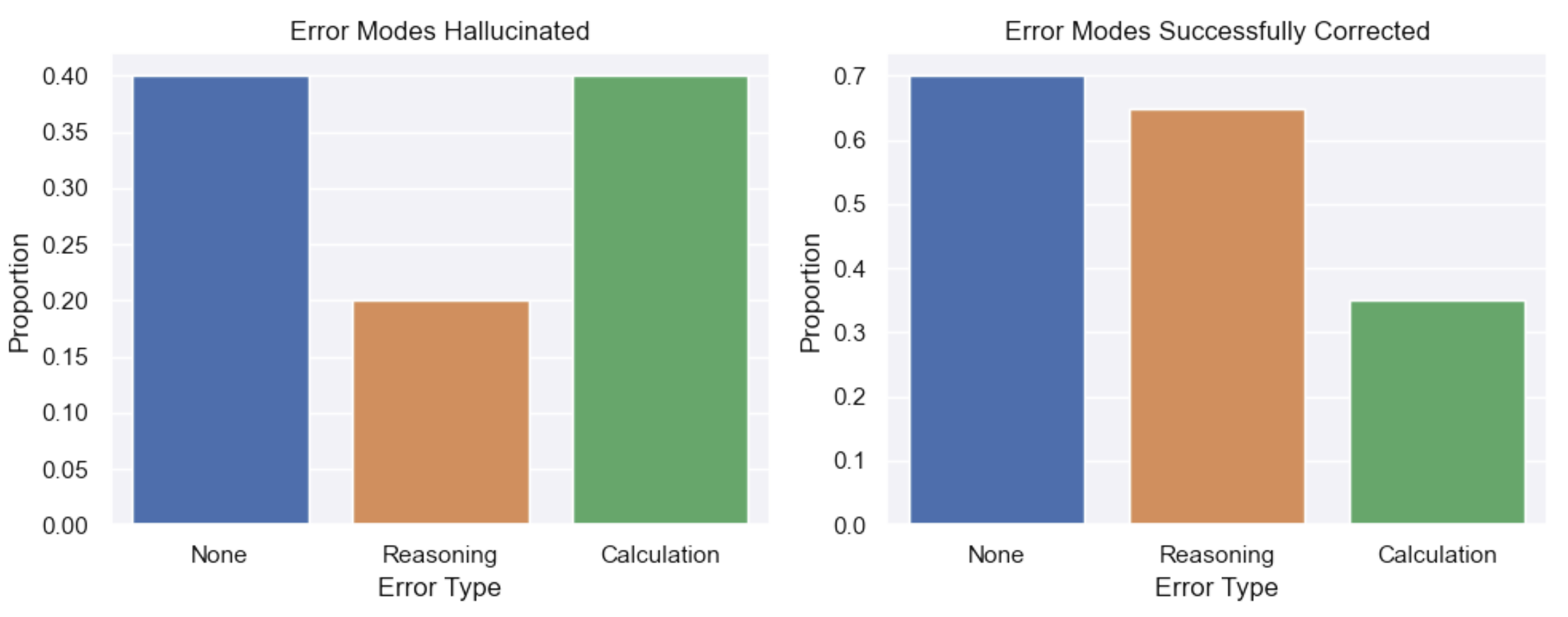

We then conducted a detailed analysis of the mistakes made by the model. In particular, we examined two categories of error modes:

- Reasoning Errors: incorrect formulas, the wrong high-level approach, copying incorrectly, and hallucinations

- Calculation Errors: small typos, incorrect algebraic manipulation, sign errors, and wrong numerical calculations

There are many nuances to the mistakes, but for the sake of brevity we decided on these two. The evaluation is somewhat subjective, but still enlightening nonetheless.

In the left plot we see the kinds of errors the model hallucinates when evaluating correct ground truth solutions. On the right are the proportion of error modes the model correctly identifies.

The model is worse at correcting calculation errors than reasoning errors

- For a correct ground truth answer

- More likely to erroneously identify a calculation mistake (40%) than a reasoning mistake (20%)

- For an incorrect ground truth answer

- More likely to catch a reasoning error (65%) than a calculation error (30%)

We had expected asking the model to double check the calculations to improve the models ability to find calculation errors, but we did not find this in practice. This also explains why previous works have found external feedback (such as a code interpreter 56) to dramatically improve smaller models self-correction.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that self-correction of mathematics is a complex behavior that smaller LLMs fundamentally lack. However, it is more the sublties of the calculation errors that the model struggles with, rather than the high-level reasoning errors – a bit like finding a needle in the haystack when you don’t know what your needle looks like. This is a promising result, as it suggests that self-correction is an emergent behavior that can be improved with larger models.

We recommend future research to delve deeper into more specific error types produced by these models to see if some can be mitigated. We also recommend future experiments involving larger models to determine whether our hypothesis—that self-correction is an emergent behavior—holds true. Considering the complexities of language and mathematics, it may be that self-correction is a higher-order cognitive process, requiring a more sophisticated level of understanding than currently possible with these models.

Because of how disaserous a runaway feedback loop could be, we recommend that much more future research be conducted to determine the best way to mitigate the effects of biased/incorrect feedback on the self-correction process before it is implemented in a real-world setting.

To learn more about our research in the finer details, you can read the full paper here.

-

Lee, Harrison, Samrat Phatale, Hassan Mansoor, Kellie Lu, Thomas Mesnard, Colton Bishop, Victor Carbune and Abhinav Rastogi. RLAIF: Scaling Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback with AI Feedback. ArXiv abs/2309.00267 (2023). ↩

-

Bai, Yuntao, Saurav Kadavath, Sandipan Kundu, Amanda Askell, John Kernion, Andy Jones, Anna Chen, Anna Goldie, Azalia Mirhoseini, Cameron McKinnon, Carol Chen, Catherine Olsson, Christopher Olah, Danny Hernandez, Dawn Drain, Deep Ganguli, Dustin Li, Eli Tran-Johnson, E Perez, Jamie Kerr, Jared Mueller, Jeff Ladish, J Landau, Kamal Ndousse, Kamilė Lukošiūtė, Liane Lovitt, Michael Sellitto, Nelson Elhage, Nicholas Schiefer, Noem’i Mercado, Nova DasSarma, Robert Lasenby, Robin Larson, Sam Ringer, Scott Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Sheer El Showk, Stanislav Fort, Tamera Lanham, Timothy Telleen-Lawton, Tom Conerly, Tom Henighan, Tristan Hume, Sam Bowman, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Benjamin Mann, Dario Amodei, Nicholas Joseph, Sam McCandlish, Tom B. Brown and Jared Kaplan. “Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback.” ArXiv abs/2212.08073 (2022). ↩

-

Gladys Tyen, Hassan Mansoor, Victor Crbune, Peter Chen, and Tony Mak. 2023. Llms cannot find reasoning errors, but can correct them! arXiv preprint arXiv: 2311.08516 ↩

-

Seonghyeon Ye, Yongrae Jo, Doyoung Kim, Sungdong Kim, Hyeonbin Hwang, and Minjoon Seo. 2023. Selfee: Iterative self-revising llm empowered by self-feedback generation. Blog post. ↩

-

Aojun Zhou, Ke Wang, Zimu Lu, Weikang Shi, Sichun Luo, Zipeng Qin, Shaoqing Lu, Anya Jia, Linqi Song, Mingjie Zhan, and Hongsheng Li. 2023. Solving challenging math word problems using gpt-4 code interpreter with code-based self-verification. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2308.07921. ↩

-

Zhibin Gou, Zhihong Shao, Yeyun Gong, Yelong Shen, Yujiu Yang, Nan Duan, and Weizhu Chen. 2023. Critic: Large language models can self-correct with tool-interactive critiquing. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2305.11738. ↩